An Intuitive Explanation of IPTW and a Comparison to Multivariate Regression Link to heading

Photo by Nadir sYzYgY on Unsplash

Introduction Link to heading

In this post I will provide an intuitive and illustrated explanation of inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW), which is one of various propensity score (PS) methods. IPTW is an alternative to multivariate linear regression in the context of causal inference, since both attempt to ascertain the effect of a treatment on an outcome in the presence of confounds. It is important to note the current evidence does not support the claim that IPTW is superior to multivariate linear models (Glynn et al., 2006). However, IPTW does confer certain theoretical and practical benefits that we will review in this post.

At the time of writing, nearly 45,000 citations in pubmed between 2000 and 2022 have been identified when querying for “propensity scor*” (PubMed query ). According to this criteria, in 2000 there were 45 citations and in 2022 there were 8,929 citations, with the number of citations increasing every year in between (PubMed query ). This increase in popularity warrants a straightforward explanation of the methodology.

Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting: Explained Link to heading

Randomized Controlled Trials Link to heading

If we want to determine the effect of a treatment on some measurable outcome, the gold standard approach is the randomized controlled trial (RCT) . In an RCT, a treatment is assigned to individuals at random. In trials with sufficiently large sample sizes, the treatment is randomized across both measured and unmeasured variables that may influence the outcome of the trial (Hariton et al., 2018). These variables will be referred to as covariates in the remainder of this post. This setup allows researchers to most closely approximate the causal impact of the treatment on the outcome. It is important to note that even RCTs are unlikely to prove causation by themselves, but they do provide the strongest evidence.

A Simple Observational Example Link to heading

Let’s begin by setting up a simple example where we obtain observational data that contains subjects who received a treatment, their sex, and their outcomes. Our goal is to determine what effect the treatment has on the outcomes. For this toy example, we will assume our data contains 8 participants, 4 male and 4 female. Additionally, the treatment is given to 2 of the 4 males as well as 2 of the 4 females as is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: A Simple Example

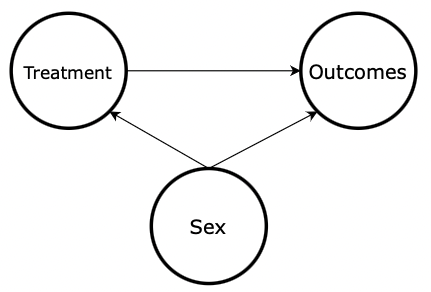

In this case, knowing the sex of the subject provides no information about whether the subject received the treatment. The overall probability of receiving the treatment is 50%. The probability of receiving the treatment given the subject is male is 50%. The probability of receiving the treatment given the subject is female is 50%. In other words, sex is uncorrelated with the treatment. The directed acyclic graph (DAG ), which shows the purported causal direction, is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: The Causal DAG

This DAG can be interpreted as showing both the treatment and sex having an impact on the outcome of the patient. However, since sex does not impact whether the treatment was deployed to a subject, there is no arrow from sex to treatment. This is what RCTs essentially guarantee in large samples. In fact, this guarantee holds for all possible covariates, even those that are not measured.

An Observational Example with Confounding Link to heading

Now we will modify the example to show what happens if suddenly sex becomes correlated with the deployment of the treatment. Figure 3 shows that females have a 75% chance of receiving the treatment while males have only a 25% chance of receiving the treatment.

Figure 3: A Realistic Example

There is still an overall 50% chance of receiving the treatment. But, knowing the sex of a subject now provides additional information about whether the subject received the treatment or not. Sex and treatment are no longer independent because the probability of receiving the treatment (50%) does not equal the probability of receiving the treatment given the subject is a female (75%) or male (25%). This is called selection bias since randomization across sex is not achieved. Now, sex is a confound , which means it affects both the independent variable (the treatment) and the dependent variable (the outcome), which will impede our ability to measure how the treatment affects the outcomes directly. Figure 4 shows the updated DAG with an arrow drawn from sex to treatment. This arrow represents the selection bias described in this section. In other words, the sex of the subject affects whether or not the subject received treatment, therefore creating a statistical confound.

Figure 4: DAG with Confounding

What to do About Confounds: Multivariate Linear Regression Link to heading

This is where we start thinking about tools we have to combat confounding, including multivariate linear regression. I will not dive into the details of linear regression here, as it is likely a prerequisite to IPTW. If you are unfamiliar with linear regression and want to take a deep dive into it, I highly recommend Richard McElreath’s Statistical Rethinking lectures and textbook . For a quicker explanation, StatQuest has a great video explaining linear regression on YouTube.

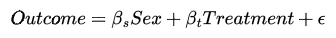

Concisely, if we were to create a linear regression of the form,

we would close the path from sex → treatment → outcomes. This is what we describe as “controlling” for sex. This would lead us to an unbiased estimate of the effect that the treatment has on the outcome since we effectively removed the selection bias caused by the sex confound.

What to do About Confounds: IPTW Link to heading

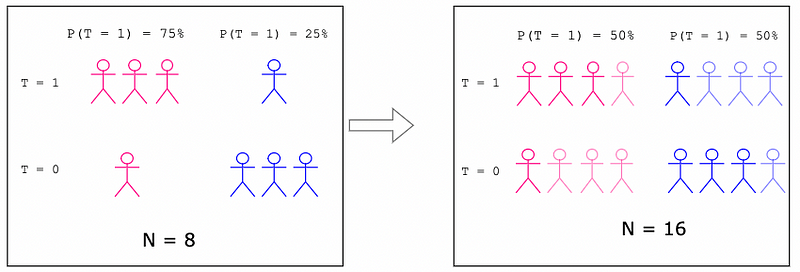

IPTW is an alternative statistical method for removing the effect of confounders. The high-level idea of IPTW is to create copies of individual observations, such that after the copies are created, the confounder no longer has a relationship with the treatment of interest. The effect is to transform the data such that the measured covariates are approximately random. The method by which we calculate how many copies of each observation to make will be the subject of the rest of this section.

I will start by explaining, in words, how we compute the number of copies, which will be referred to as weights from here onward. If the explanation of the procedure is unclear, Figure 5 will provide an intuitive visual explanation of the weighting scheme.

The mechanics of computing this weighting is as follows:

- For each observation i, find the probability, p, that it ends up in the treatment group it is in (Chesnaye et al., 2022 para 9). This is where the “probability of treatment” comes from in inverse probability of treatment weighting.

- Compute the weight, w, for the individual observation as 1/p. This is where the “inverse” comes from in inverse probability of treatment weighting (Chesnaye et al., 2022 para 9).

- Create “copies” using these weights.

We will compute the weights for the females who received the treatment in our example. First, we need to find the probability that each female in the treatment group received the treatment. Since 3 of the 4 females received the treatment, we know this probability is 75%. Then, we compute the weights for each of these three females by inverting this probability. So, 1/0.75 equals 1.333. Finally, we create the “copies” using this weight. Since we have 3 females, 3 x 1.333 = 4. In other words, we will end up with 4 females. See Figure 5 for a clear visual explanation of this procedure.

Figure 5: Computing IPTW Weights

This process has increased the importance of some observations more than others. The effect is to both increase the sample size and to balance the covariates. We call this a pseudo-population since we are effectively adding individuals to the sample by using this weighting scheme. Figure 6 shows the effect of using these weights on the pseudo-population.

Figure 6: Covariate Balanced Pseudo-Population

The effect of using these weights is to control for confounding variables by structuring the pseudo-population in a way that the treatment no longer is dependent on the confounder. In this pseudo-population, knowing the sex of a subject no longer adds any information about whether the subject received the treatment or not. This is what we refer to as balancing the covariates.

Now, if we redraw the causal DAG as is shown in Figure 7, we will remove the arrow from sex → treatment. Sex affects the outcome but it no longer affects the treatment. Therefore, we have removed the confound.

Figure 7: DAG Without Confounds

Rest and Off Ramp Link to heading

If you have made it this far, good job. This is a great spot to stop. You now have a solid conceptual basis for understanding IPTW. The next two sections will build upon this basis with two slightly more advanced topics in IPTW. They will include:

- Stabilized IPTW, and

- Calculating propensity scores

If you want to forego these sections, feel free to. However, it might be worthwhile to read the Comparing IPTW to Traditional Multivariate Models and Conclusion sections.

Stabilized IPTW Link to heading

In the IPTW example, recall how we increased the effective sample size from N=8 to N=16. This will be summarized in Figure 8.

Figure 8: Increased Sample Size

While we no longer have unbalanced covariates, we introduce a new dilemma. As the sample size increases, statistical tests are more likely to find an effect. This is due to properties of the central limit theorem . A larger sample means that statistical tests we apply to the sample have greater statistical power . By artificially doubling the sample size, we are artificially inflating the probability that we find our treatment has an effect on the outcomes (Xu et al., 2010). This is due to a phenomenon called repeat sampling.

To illustrate why repeat sampling is problematic, consider 2 supposedly fair coins that are flipped 4 and 8 times, respectively. For this example, each coin produces a head on every flip. The probability that the first coin produces 4 heads is 6.25% and the probability that the second coin produces 8 heads is 0.39%.

The probabilities we computed for our two different coins are analogous to p-values . They represent the probability of the event happening given the coins are fair. Now we want test whether the fair coin assertion is true in the presence of the observed data. We will use a hypothesis test where the null hypothesis is that the coins are fair and the alternative hypothesis is that that the coins are biased.

Consider the coin that produced 4 heads. The probability of this event (the p-value) is 6.25% if we assume the null hypothesis to be true. This p-value typically does not provide convincing evidence that the coin is biased. Normally, we would require a 5% or smaller p-value. Now, imagine we artificially double this sample by weighting each flip by the value 2 (which is a direct analog to how IPTW works). We know the probability of 8 coin flips all producing a head is 0.39%, which is sufficient evidence to claim the coin is biased and to reject the null hypothesis. However, the data we obtained only contains 4 coin flips worth of information. Therefore, we have inflated the probability that we reject the null hypothesis (the coin is fair) in favor of the alternative hypothesis (the coin is biased), also known as a type I error . This is precisely the issue we run into with IPTW.

To remedy this artificial increase in sample size, we will introduce the stabilized IPTW. Simply put, instead of calculating the weights as

we will compute the weights as

Figure 9 will show how we compute the numerator in the stabilized weighting scheme.

Figure 9: Stabilized IPTW Numerator

Figure 10 will show how this updates our weighting scheme such that we do not increase the pseudo-population size to be substantially larger than the actual population in the original data.

Figure 10: Computing Stabilized IPTW Weights

The effect of using this stabilized weighting scheme is that the pseudo-population is no longer so much larger than the original population, as is shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11: Stabilized Covariate Balanced Pseudo Population

Since we no longer increase the size of the pseudo-population in comparison to the original population, the probability of a type I error (false positive) is not inflated.

Calculating Propensity Scores Link to heading

Calculating the probability that a subject receives the treatment, which is also known as the propensity, is rarely as simple as it seems in the previous examples. To illustrate, let’s add an additional covariate, age, to our example and see how it plays out.

Figure 12: DAG with Two Confounds

Quickly inspecting this causal DAG, we note that sex still confounds the effect of the treatment on the outcomes as we saw in previous examples. Additionally, age is added as a confound. Unfortunately, since age is a continuous variable, we cannot draw the probability of treatment diagram as we did before. In fact, we will need a new method altogether for computing the propensity.

This is where we will leverage logistic regression . I will not do a deep dive on how logistic regression works in this post. If you are unfamiliar with logistic regression, I recommend watching the StatQuest video on logistic regression for a very tractable overview. The key takeaway is that we can use logistic regression to calculate the propensity score for receiving the treatment given the covariates, sex and age.

Once we use the logistic regression to compute the propensity scores and reweigh the data, it is crucial to inspect the weighted covariate distributions to make sure they are balanced. Now that additional complexity has been added by estimating propensity scores using logistic regression, we need to check the goodness of fit (Borah et al., 2013). This will simply involve checking to make sure that the distributions of age and sex are approximately similar for those who received the treatment and those who did not.

Comparing IPTW to Traditional Multivariate Models Link to heading

As mentioned in the introduction, the gold standard in causal inference is the RCT. In the real world, it is not always feasible to construct a full RCT, though. So, we are left with using statistical techniques that approach RCTs, including multivariate linear regression or PS models, like IPTW. IPTW is great because it attempts to create covariate balance among observed covariates, which is what an RCT guarantees. In contrast, multivariate linear regression does not attempt to balance covariates at all. However, “there is no evidence that an analysis utilizing propensity scores will substantially decrease bias from confounding, relative to conventional estimation in a multivariate model" (Glynn et al., 2006 para 31).

Though IPTW maintains some theoretical advantages over linear regression, “There is little evidence for substantially different answers between propensity score and regression model estimates in actual usage”(Glynn et al., 2006 para 8).

Naturally, the question of why researchers would want to use IPTW instead of linear regression arises. I will briefly review some of these reasons below.

1. PS methods allow researchers to use a principled method for trimming the study population

Figure 13: Exposure Propensity Score — Credits: Glynn et al, 2006.

In Figure 13, the dotted curve represents the distribution of propensity scores for individuals who did not receive the treatment. The solid curve represents the distribution of propensity scores for individuals who did receive the treatment. In the left tail of the untreated distribution and the right tail of the treated distribution, note how there are individuals who are never treated or always treated, respectively. Removing these individuals from the study population confers theoretical benefits since these observations “may be unduly influential and problematic in a multivariate analysis because of minimal covariate overlap between [treated] and [untreated] subjects” (Glynn et al., 2006 para 16)

2. PS methods can elucidate how the treatment interacts with one’s propensity to receive the treatment.

By stratifying subjects by propensity scores, it is possible to identify whether the treatment’s efficacy varies depending on which strata of propensity scores each subject is in.

3. PS calibration can improve robustness of a main study

Consider an example where we have two studies: a main study and a validation study. Both are designed to evaluate the same treatment’s effect on an outcome. The main study has a substantially large sample size and the validation study is smaller. In the main study, there are predictors that are omitted due to not being measured. Therefore, the main study’s propensity scores will suffer from omitted-variable bias . However, the validation study “may have a more reliable estimate of the propensity score” (Glynn et al., 2006 para 20) if it contains more detailed predictors that correct for the omitted variable bias of the main study. It is then possible to use the validation study to calibrate the propensity scores in the main study and reduce bias (Stürmer et al., 2005_)._

Conclusion Link to heading

To conclude, we have reviewed the mechanics of IPTW. The primary goal of IPTW is to ensure that covariates are balanced across the treatment groups such that confounding by measured covariates is reduced as much as possible. Additionally, we reviewed two more complex topics in PS methods, including stabilized weights and computing propensity scores. Finally, we briefly discussed a few theoretical benefits of using IPTW instead of multivariate linear regression. The main purpose of this article is to provide the reader an intuition about how IPTW works since its prevalence as a statistical method has dramatically increased in the last 20 years. I hope this overview was helpful!

All images unless otherwise noted are by the author.

References Link to heading

[1] B. Borah, J. Moriarty, W. Crown, and J Doshi, Applications of propensity score methods in observational comparative effectiveness and safety research: where have we come and where should we go? (2013), Journal of Comparative Effectiveness Research

[2] E. Hariton and J. Locascio, Randomised controlled trials — the gold standard for effectiveness research (2018), British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology

[3] N. Chesnaye, V. Stel, G. Tripepi, F. Dekker, E. Fu, C. Zoccali, K. Jager, An introduction to inverse probability of treatment weighting in observational research (2022), Clinical Kidney Journal

[4] R. Glynn, S.Schneeweiss, and T. Stürmer, Indications for Propensity Scores and Review of their Use in Pharmacoepidemiology (2006), Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology

[5] S. Xu, C. Ross, M. Raebel, S. Shetterly, C. Blanchette, D. Smith, Use of Stabilized Inverse Propensity Scores as Weights to Directly Estimate Relative Risk and Its Confidence Intervals (2010), Value in Health

[6] T. Stürmer, S. Schneeweiss, J. Avorn, and Robert J Glynn, Adjusting effect estimates for unmeasured confounding with validation data using propensity score calibration (2005), American Journal of Epidemiology

By Jonah Breslow on January 11, 2023 .